If you have been a regular reader of this blog, you may recall that we utilize game feeders here at the ranch on a year round basis. Notwithstanding the temporary feelings of angst regarding wildlife feeding (detailed in the previous post Birds Of A Feather), we have enjoyed the benefits that having feeders provides us, namely, regular visits from the local wildlife.

Having game feeders operating reliably full-time has proven to be more of a challenge than I would have previously thought. In a previous post entitled Feeder Maintenance Time Again, I pointed out my experiences providing a reliable source of power to the feeder units. One of today’s chores was to replace the batteries in two feeders and refill them both with deer corn, so I thought I would take you along to see what this is all about.

The feeder pictured above is a tripod mounted plastic drum which utilizes a block-and-tackle hoisting mechanism. The drum holds three bags, or 150 pounds of deer corn.

In the photo above, you see the actual feeder timer and motor assembly, all housed into a neat, compact package. The 6 volt alkaline battery that we are replacing hangs from two alligator type clips on the end of a short set of wires. In fact, the wires are so short that it is actually quite difficult to attach the alligator clips onto the battery terminals. After finally managing to attach the clips to the battery, it becomes a comical sight to watch me try to push the battery back up into the housing and attach the bottom cover plate with the four tiny sheet metal screws provided. It usually takes me several tries, with frequent interruptions as I search for the small parts that invariably drop to the ground (dang gravity).  If only the people who design these things were required to actually use them in the field, this probably wouldn’t happen.

In the photo above you can see the funnel tube (coming down from the drum) and the spinner plate that the corn comes to rest on. Some of the previous feeders that we have owned were produced with plastic funnels and spinner plates. The varmints of the area soon learned to chew through the plastic parts, thus allowing the entire contents of the drum to spill out onto the ground. One manufacturer even has the audacity to sell replacement parts fabricated out of metal, even while selling new feeder units with the useless plastic parts. Even with the metal parts, eventually the larger varmints manage to bend the spinners to the point that the corn is released to the ground, and the feeder unit fails to operate due to the bent spinner plate. The solution to this problem is to surround the entire feeder assembly with a varmint-proof enclosure, as is shown in the photo above. There are after-market enclosures for sale by various manufacturers. It would be nice if they were included as a standard item on all complete feeder kits, but they are not. A word to the wise – if you buy or build your own wildlife feeder, spring for an optional varmint guard.

In this photograph you can see that this particular feeder drum lid is held in place by a sturdy expansion hoop that is fitted with a cam-lever type closure system. This system works great – it is quick and can be operated in all kinds of weather easily. You can also see that the drum is made from plastic materials. The advantage of the plastic is that it will not rust or corrode. The obvious disadvantage to the plastic materials is that they are not resistant to the sharp, persistent teeth of varmints. You can see in the photo above that I have had to patch up the lid with duct tape after some critter chewed its way into the drum of delectable apple flavored deer corn. Several times. If the people who designed feeders were compelled to actually use and maintain them, we would probably see an end to plastic drum lids.

The great advantage of this tripod feeder unit is the block-and-tackle hoist system that it incorporates. By simply lowering the drum to ground level, it is relatively easy to fill the drum to capacity with the necessary three bags of deer corn, as you can see from the photograph above.

After the drum is filled, the block-and-tackle hoist system makes it a breeze to lift the corn-filled drum back into the raised position. It is a simple, effective system for easing the job of filling feeders, which can be a back breaking task, as you shall soon see.

The type of feeder you see above is a stationary tripod style of feeder. This feeder drum and lid are built entirely from metal and the feeder unit is enclosed in a varmint cage, so there is no possibility of varmints chewing their way into the corn supply. Because the drum does not have to be hoisted up off the ground after filling, it can be built to accommodate a larger supply of corn. Whereas the first feeder has a capacity of 3 bags of corn (150#), this feeder has a capacity of 4-1/2 bags of corn (225#), so the interval between fillings is longer.

The picture above shows the pitiful lid closure mechanism that this manufacturer employed. To remove the lid, you must first completely remove the bolt from the lid retaining hoop. This requires the use of a screwdriver (which I store on top of the lid for convenience) to remove the bolt, whilst stretching up to reach it’s lofty height. In the warmer months this is merely an inconvenience, but in the depths of winter, when the thermometer indicates unspeakably low temperatures, and you are trying to remove the lid while hungry deer peer out at you from the forest edge, it is a royal pain-in-the-butt. If the people who engineered these closures were required  to operate them regularly in January, we would probably not see these in use anymore.

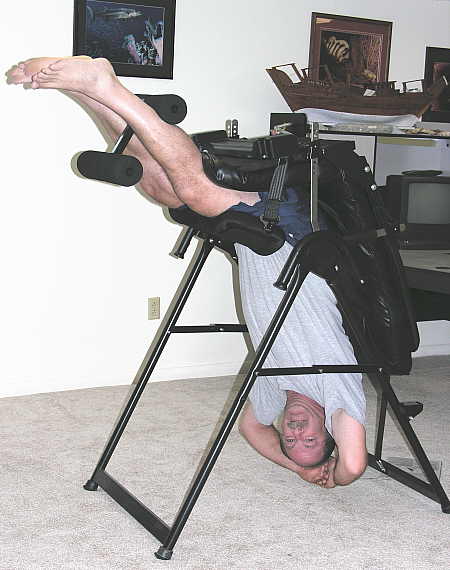

I have saved the very best for last. To fill this type of tripod feeder requires the strength, height, and stamina of Shaquille O’Neal, and not the tired, worn out body of this Ramblin Rancher, as you can clearly see from the following picture.

To get the corn into the feeder requires a sort of “clean ‘n jerk” technique, as used in Olympic style weight-lifting. First, using your knees as best as possible, the sack is snatched up off the floor in one fluid motion, while at the same time, your body comes down into position so that the 50# sack of corn comes to rest on your shoulder. Now that the corn is held up by your shoulder, straighten your legs to full extension, and then lift the sack as high as possible over your head, hoping to aim it well enough so that the corn ends up in the drum, and not on the ground. If all goes well, then repeat this procedure four more times, before heading for the house to rest your aching back for the balance of the day! If the designers of wildlife feeders were required to fill feeders with corn on a regular basis, I’ll bet these types of stationary tripod feeders would disappear. But then again, what do I know?