Here it is, Labor Day weekend in the Ozarks, and this morning I am found to be doing the very thing one would expect an Ozarker to be doing on a holiday weekend – surveying trees. Not just any trees, but Black Walnut trees, which thrive in this part of the Ozarks. The Black Walnut produces a nut that is used in cooking, and the shell and hull of the Black Walnut have commercial uses as well. Every fall, Hammons Products Company sets up 250 collection stations across 12 states, where the Black Walnuts are purchased from the local collectors. The following photograph shows a Black Walnut tree as it appeared in early August.

You will see from the photo above that the Black Walnut tree is not particularly distinct from a distance in the middle of summer. They are easy to identify up close, but from far away they look much like many other trees that commonly grow here. One of the things that I have noticed about the Black Walnut is that it is one of the last trees to leaf out in the spring, and it is the first of our local trees to drop it’s leaves at the end of summer.

The leaves that appear on the ground in the photo above are from a Black Walnut tree. The picture was taken this morning, September 3. No other trees in my area are shedding leaves yet, however there is a brown carpet of leaves below the Black Walnuts. The leaves that remain on the tree itself have now turned either yellow or lime green. So why, you may ask, do I care so much that the leaves of the Black Walnut are the first ones to change color and drop in the fall? Because when the Walnut trees are the only ones in the forest that exhibit this coloration, they become easy to spot from a distance. In fact, as the following photograph shows, the Black Walnut trees stand out like a beacon in the night, they are so distinct.

Now that the Black Walnut trees are easy for a non-botanist like myself to identify from a distance, I can proceed to make the preparations that will facilitate a successful harvest of Black Walnuts from our property. The first step is to map all of the Walnut trees on our property that are currently bearing nuts. Regular readers of this blog might recall a previous post entitled If They Can Do It, So Can I, in which I introduced you to my “super-duper, multi-purpose, portable cartographic data collection machineâ€Â (SDMPPCDCM). Using this device, I can easily drive around the property locating the Black Walnut trees that now stand out like a sore thumb, and examine each tree to see whether or not it is bearing nuts this season. The following photograph shows a Black Walnut tree that is currently loaded with walnuts.

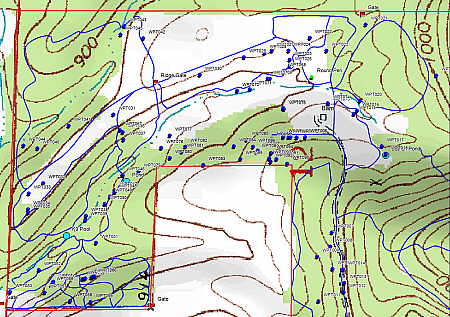

When I find a Black Walnut tree that has produced nuts, such as the tree above, I record the tree as a way-point in my GPS mapping system. After pinpointing the coordinates of all the nut bearing trees, it is a simple matter to plot this data on a topographic map of the property. The results are shown in the following screen capture from my mapping program. The data layer that is selected below shows the results of this little exercise. The location of all the nut bearing trees are clearly shown on the map (as blue way-points).

I do not know how many Black Walnut trees we have on our property. My best estimate is between 200-300 trees. This season I located 94 Black Walnut trees that are bearing nuts in a prolific manner.Â

Step two of the Black Walnut harvest will be for me to get out the tractor and bush-hog the areas surrounding all of the nut bearing trees. The goal will be to ensure easy access to the trees by Jasper Smith, my octogenarian friend who collects the Black Walnuts from our ranch each fall. You may recognize Jasper Smith as the same friend who also keeps and courses bees as an avocation (Jasper, and photos of a “bee tree hunt” can be found here). Jasper is an amazing man with amazing stories. I will save my comments about him for a future post, when he comes around to gather the fallen walnuts. which will be step three of the Black Walnut harvest here. Stand by for future posts on the subject.